Our environment has a profound effect on us. It can impact everything from our level of concentration and productivity to our health and emotional wellbeing. Yet many schools aren't designed in a way that maximises learning outcomes, fosters community, encourages play, and prioritises student and teacher wellbeing.

Could your school be one of them? To help you, here are the five key issues in education design that impact learning and wellbeing that we identified through analysing over 140 schools in Australia.

1. Classroom layouts prevent learning opportunities

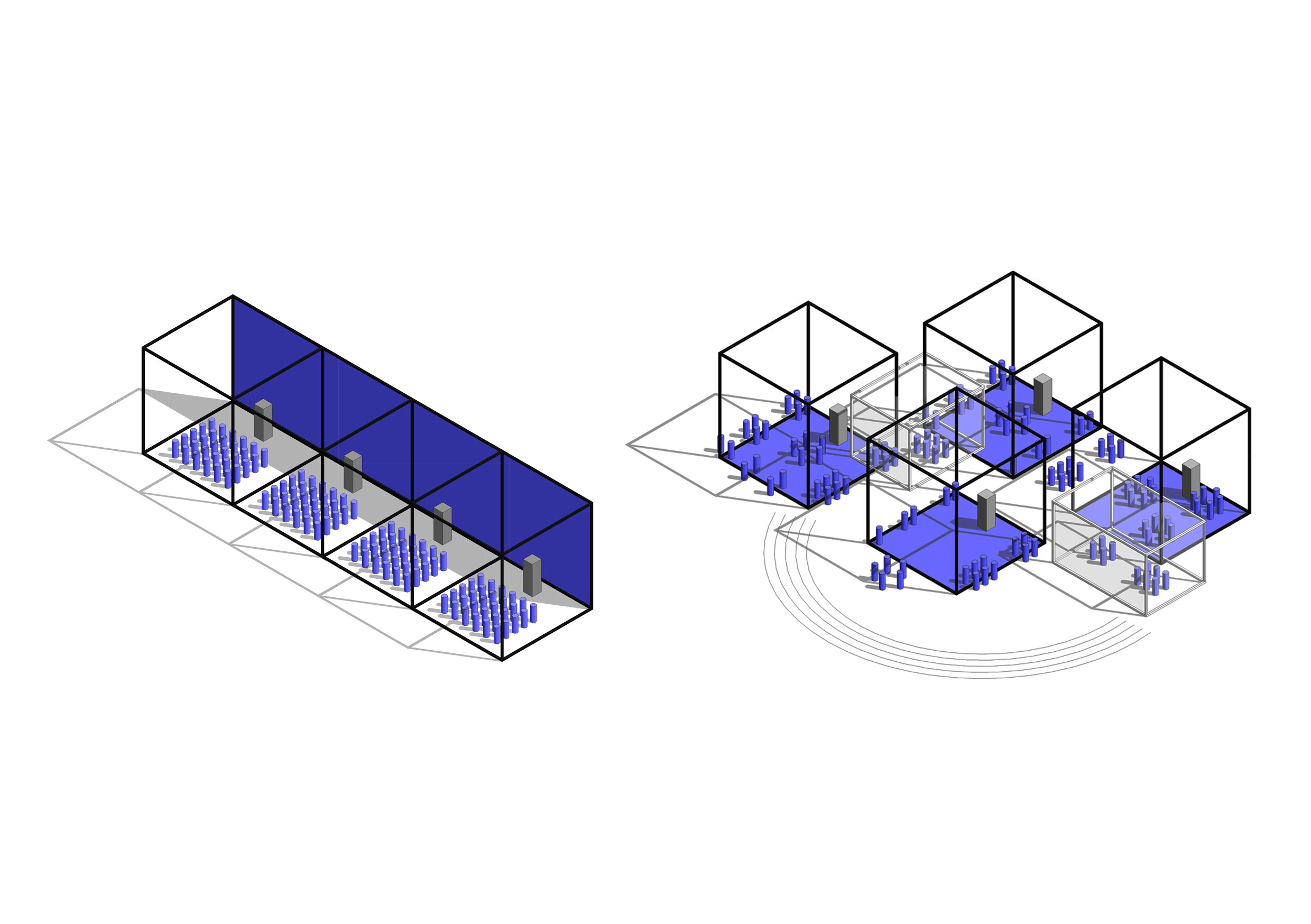

Gone are the days when every classroom layout has rows of desks facing the teacher and whiteboard. With each child learning differently, it’s important that the modern classroom features flexible learning areas for students to be able to learn in multiple ways – with the teacher, by themselves, and in varying group sizes through their peers.

For this to happen effectively, classrooms spaces need to be designed to have different areas that cater for collaborative work and discussion, allow for quiet individual work and retreat, and encourage focus time with the teacher at the front of the room. Open planning, breakout areas and flexible furniture are key to creating this flexibility within the classroom.

2. Children don’t have the flexibility to learn outside

While children thrive in routine, their performance can be impacted by working in the same environment all the time. By creating outdoor classroom environments, teachers and students can venture outside when the weather allows for different learning opportunities.

Combining adaptable indoor learning spaces with flexible outdoor spaces that are large enough for full class groups, students are given many varied opportunities for interaction, performance, collaboration, and connection to nature.

This not only boosts student engagement, but it also minimises costs of lighting and air-conditioning while providing greater connection to the landscape and better working conditions.

3. There are inadequate views to landscape from classrooms

Increasing the proportion of natural landscape within our immediate environments is key to improving both our physical and emotional health. In a study into ‘school landscape environments,’ it was suggested “that the function of schools’ landscape has significantly related to efforts of assisting the learning processes and nourishing environmental appreciation among students” (Ali, Rostam & Awang, 2015).

But unfortunately, some classrooms (even on the ground floor) don’t have adequate views to landscape. Increasing views to landscape, which can encompass a variety of natural and constructed spaces including open fields, gardens, shelters and open pavilions, reflective areas, and water bodies to name a few, can be a quick and easy way to improve student learning and wellbeing.

4. The inability for children to run and use their energy when needed

It’s no secret that physical activity is good for our health and improves our ability to think clearly. Yet the design of many schools and classrooms don’t allow children the opportunity to have regular times to move their body to increase their learning potential.

Throughout our consultation with teachers, we heard time and time again that the traditional classroom layout of desks facing a teacher doesn't allow kids an outlet for their abundant energy. This can lead to children being fidgety, distracting others or misbehaving.

The modern classroom model needs to allow space within the classroom inside and outside for children to use energy when they need to while still being a part of the class.

5. Carbon Dioxide build up from a lack of fresh air

While many schools install air-conditioning for the comfort of students and teachers, what many people are unaware of is that the quality of air can be dramatically affected. In environments with split system air-conditioning and no fresh air intake, air is simply moved around the room but not replaced, leading to a build-up of Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) throughout the day, which affects the cognitive ability and learning capability of students in the classroom.

In 2016, a study done by researchers at Harvard and Syracuse University found that human cognitive function declined by about 15% when indoor CO₂ reached 945 parts per million and crashed by 50% when indoor CO₂ reached 1,400 parts per million. Environments with split system air-conditioning can quickly reach these levels, especially after lunch when 30 sweaty kids re-enter the classroom after running around for an hour.

It’s a conundrum, isn’t it? We put students into classrooms and exam rooms that are air-conditioned for their comfort only to create the worst possible air quality for them to perform and compete against other schools in.

The good news is that through sustainable initiatives both the comfort and air quality of classrooms can be improved. While there are times when air-conditioning must be used, there are times when air-conditioning could be minimised by using a more effective passive ventilation design (like louvres) that will allow greater fresh air and breezes through the classroom. Ducted systems with fresh intake are very important in the classroom as are CO₂ monitors for any rooms that already have split system units installed.

Do measures like this make an impact, you might ask? A study done by the United States Environmental Protection Agency that examined the costs and benefits of green schools for Washington State estimated a 15% reduction in absenteeism and a 5% increase in test scores.

If you would like to book a School Audit to see how your school performs in these areas and more, call us today on (07) 3870 9700 (Brisbane) or (03) 8547 5000 (Melbourne).