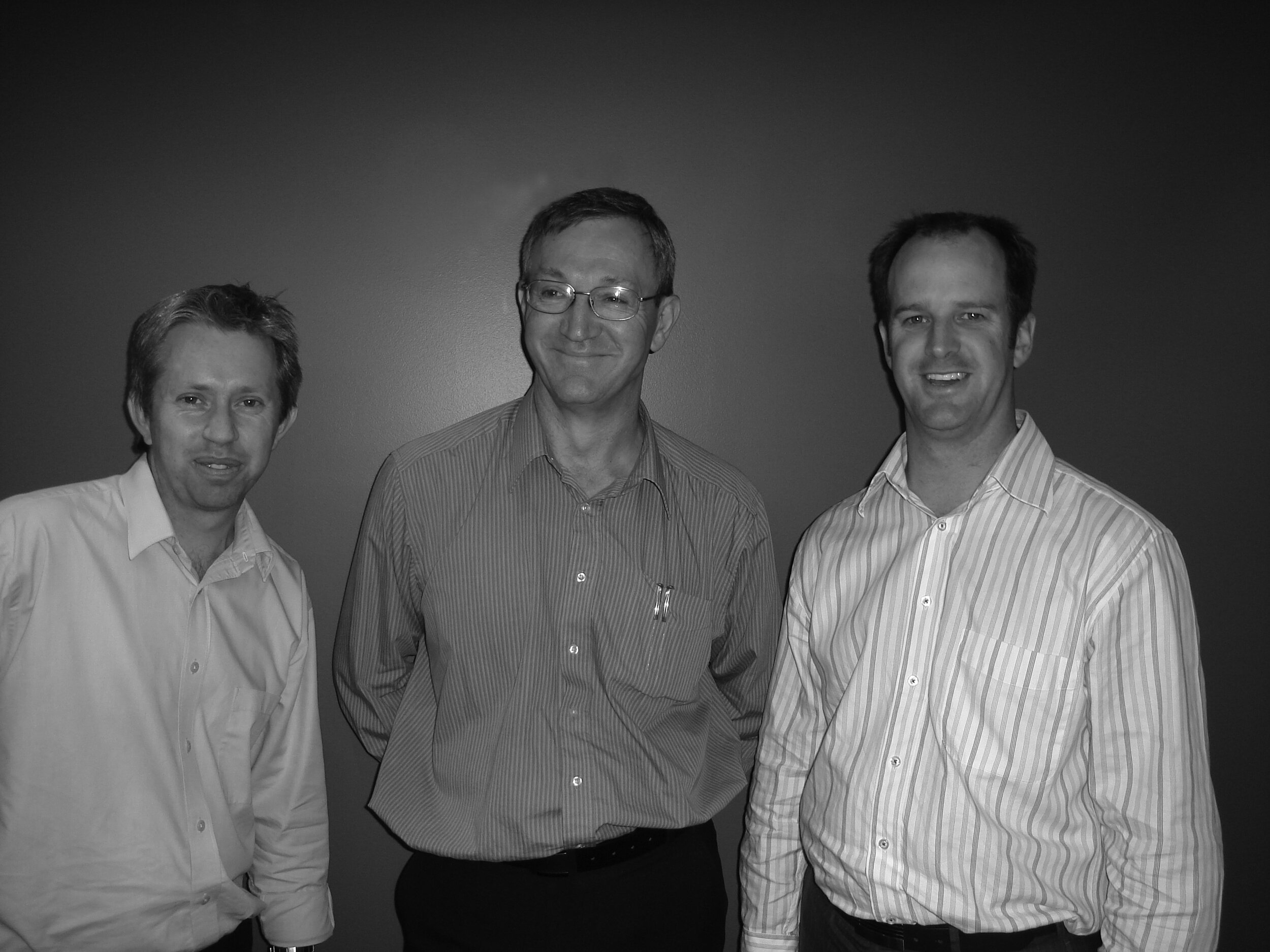

2020 marks a special year in the career of our Directors, Phil Jackson and Kavan Applegate - they both celebrate 25 years at Guymer Bailey Architects. After celebrating Kavan’s anniversary early this year, this week is Phil’s turn.

To mark this occasion and celebrate the incredible contribution Phil has made to Guymer Bailey Architects, we reached out to some of his friends, team and clients to hear what they had to say about him.

“25 years - congratulations! Are you sick of me yet?! I’m remembering long, long hours on uni assignments together (and you realising we needed to completely redesign a railway station 3 weeks before it was due) and loads of wonderful projects we’ve worked on over the years. I couldn’t be prouder to be your business partner, and dear, dear friend.”

“I clearly remember the day you started as a student architect with Tim and I at GBA, Phil. I watched you develop as you finished your degree and took up Project Architect roles often with me on my projects, plus many of your own over the years.

I recognised your design talents early and saw a great future for you. I really enjoyed working with you over the last 25 years. When GBA joint ventured with Architectus to go after the Brisbane Supreme Court, Phil you happily took up the project with me and we spent much time together out of the Architectus office in the city. You have won architectural awards for your own projects too.

When Tim and I decided to sell GBA to our staff, I was personally pleased to see you take up the challenge to be a part owner of GBA and to see you with Kavan Applegate and Paul Mathieson develop the company into what it is today.”

“Phil congratulations on a successful 25 years. It is rare to work with someone that sets an enviable standard – Phil is one such example. He listens, considers, and relentlessly works to get a high quality outcome and always has time for all team members. His professionalism and ease of interaction makes him a delight to work with and I always feel we will outperform when working together.”

“Congratulations Phil for all the years of work and leadership at GBA - and you still look so young! ...and are still able to laugh! How can you work so hard and long and still find humour and delight? Thank you for the tireless work you put in for the Catholic schools especially the LLS ERaMPs! Your dedication, inspiration and perspiration and the calibre of the team you applied to that big project were beyond anything any client should ever expect. Your ability to engage with, consult and sort out that herd of cats and the graciousness with which you did it was simply extraordinary. I am sure it was what you might consider your “ordinary” modus operandi and if that is so you have many happy clients I am sure. Cheers and all the very best.”

“Congratulations on 25 years Phil, it has been an absolute pleasure to work for a great company under your leadership. Over the last 12 years I’ve learnt so much from you and I am often overwhelmed by your dedication, passion, and knowledge. Your calm approach to any challenge is a real asset and your understanding and drive for sustainable outcomes admirable.”

“I remember coming to my job interview where I briefly met you Phil yet walked away with a really good feel, mostly due to your nature. It’s crazy to think you have been here for 25 years - and that you’re younger than me!! GBA was your first and only right?! So, it must be time for you to make a change, get out and broaden your horizons 😉!

A few words that I think sum you up Phil (in no particular order):

Fair

Calm

Can laugh and take a joke

Extremely ethical

Reserved, unassuming and avoids the spotlight

Modest

Good guy and excellent leader

Great dad (not sure about husband…wink wink)

Trusting

Way too hard a worker!

… and without doubt an amazing designer

I wouldn’t want to work any where else. The effort that you and Kavan make to ensure GBA is a great place to work is second to none. From the space we work and collaborate, to the ‘social bits’, both in and out of the office. It’s been challenging but definitely enjoyable working with you. Congratulations on your accomplishments and where you have come in 25 years! It’s no mean feat!”

“Phil Jackson congratulations on your 25 year anniversary. We love your work, your problem solving skills are always on point and delivered with a smile. It’s a pleasure to work with a consummate professional who I would never hesitate to recommend”

“Thank you Phil for the opportunity to work together on Mary Cairncross Scenic Reserve. You’re a gifted designer and exceptional manager with a great team. Congratulations on 25 years with GBA - you’re a star! ”

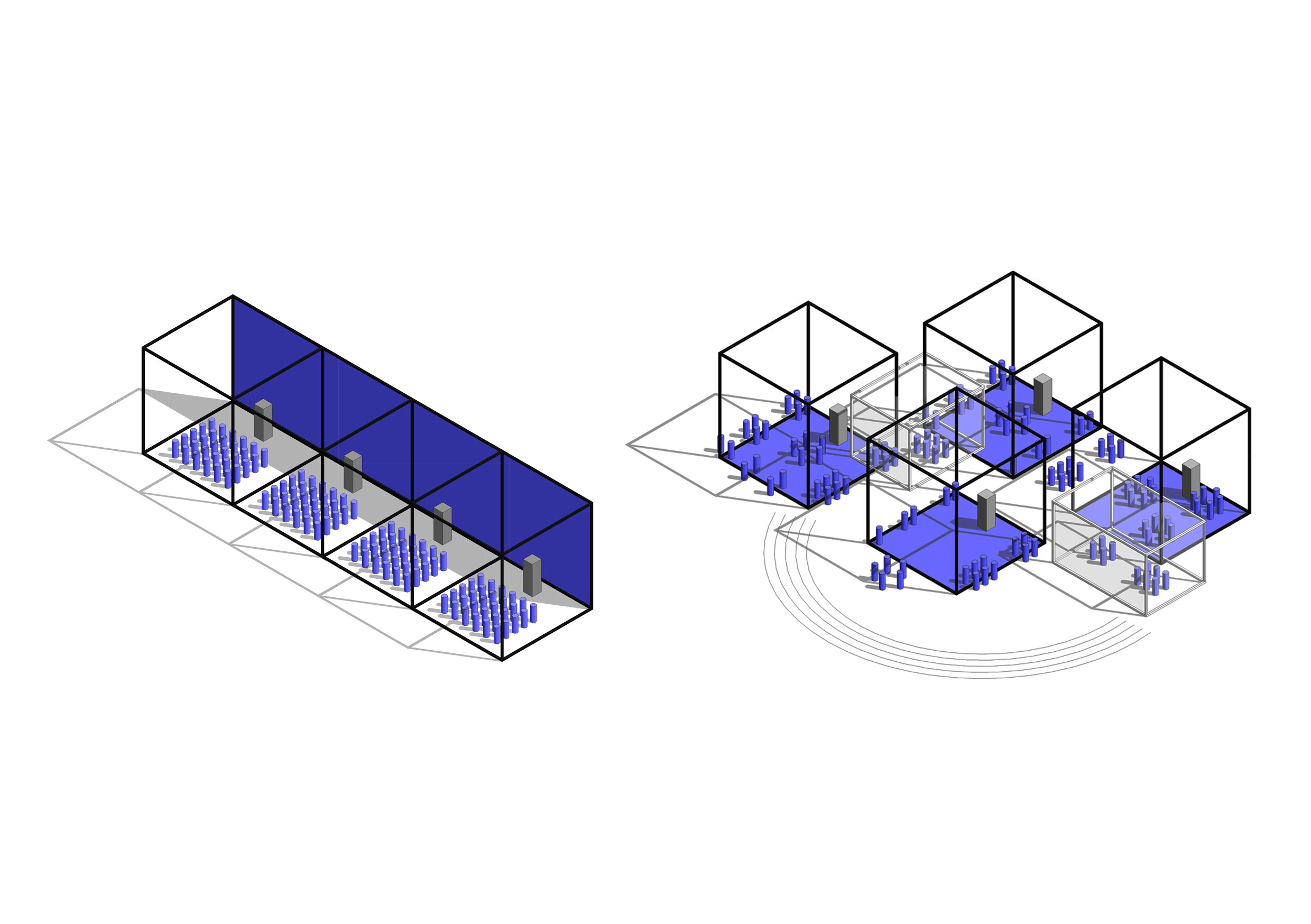

Phil’s impressive career has included designing many award-winning projects including the Mary Cairncross Scenic Reserve Rainforest Discovery Centre, Brisbane Supreme and District Courts, Maroochy Arts and Ecology Centre and the Caloundra Courthouse and Watchhouse. We’ve included some of our favourite projects that Phil has worked on below.

Phil, thank you for your leadership, design nous and passion that is seen through all that you do. Here’s to the next 25 years!